Review by Bill Doughty

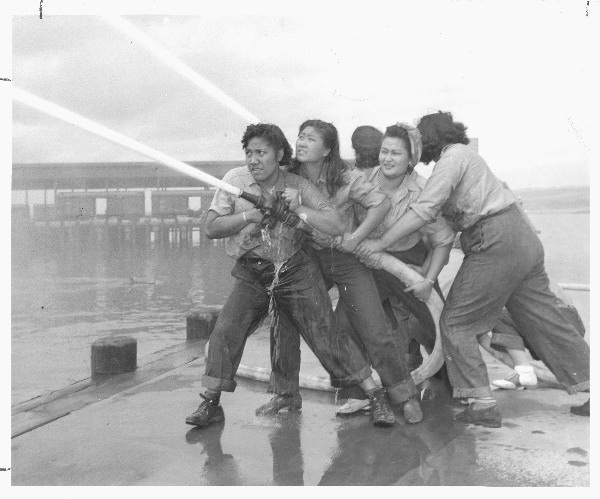

In an iconic photo, four Asian American Pacific Islander women at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard train in firefighting. Long mislabeled as taken during the attack of Dec. 7, 1941, the photo in fact portrays some of the strong women who applied to support the Navy’s war efforts in the wake of that attack. From left to right: Elizabeth Moku, Alice Cho, Katherine Lowe, and Hilda Van Gieson.

Over time, history usually has a way of sorting out fact from fiction.

|

| Rear Adm.Grace Hopper, "Mother of Computing" |

Among the women profiled are some we featured in Navy Reads posts: Rear Adm. Grace Hopper, Ada Lovelace, Rachel Carson, Marjory Stoneman Douglas, Margaret Chase Smith, Malala Yousafzai, and Maya Angelou. This book includes mini-biographies of both famous (Clara Barton, Helen Keller, Ida B. Wells, Maya Lin, Gabby Giffords, Greta Thunberg, and Venus and Serena Williams) as well as less-well-known women (Rigoberta Menchu Tum, Dr. Gao Yaojie, Nelba Marquez-Greene, Wangari Maathai, and Jineth Bedoya Lima).

|

| Chelsea and Hillary Clinton, 2011 |

Chelsea writes, “I learned of Grace (Hopper) in 1996, when the navy named a new ship the USS Hopper (DDG 70) in her honor … I learned even more about her when I spoke many years later at the Grace Hopper celebration, the largest gathering of women technologists in the world.”

Former First Lady, senator, and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton reflects about the suffragists who knocked on the door, marched in the street, and fought for women to be able to vote in the United States one hundred years ago. That right was guaranteed with the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, but it was a right that took decades to apply to women of color:

“Reading the words of the Nineteenth Amendment today, it’s hard not to wonder why it took so long” ‘The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex. Congress shall have the power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.’ But, of course, it was a long struggle because it was about so much more than the right of women to vote. It was about race, class, and deeply held cultural and religious views about women’s subordinate roles to men in society. It was about men’s –– and some women’s –– insecurities and fears of the unknown. These challenges are still present today.

The franchise –– the basic right of citizenship –– is still being fought over between those of us who believe every citizen should be able to vote and have that vote counted, and those who want to restrict the vote by erecting barriers against people, largely still based on race.”

|

Celia Ou, a graduate student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, monitors computer screens displaying detailed sonar imaging of the ocean floor aboard the Auxiliary General Oceanographic Research (AGOR) vessel R/V Sally Ride, Dec. 15, 2016. (John F. Williams)

Nearly all the Gutsy women featured in this book faced and overcame some kind of obstacles of discrimination. Chelsea Clinton says this about space pioneer astronaut Sally Ride, the first American woman in space (in 1983) and a champion of STEM education for young people worldwide:

“Even after her death in 2012, Sally Ride kept breaking barriers. She came out as a lesbian quietly, without fanfare … Not long after her death, Tam [O’Shaughnessy, her partner of 27 years] received a call that surprised her, from Ray Mabus, then secretary of the navy. The navy hoped to honor Sally by naming a research vessel after her. Secretary Mabus was calling to ask whether Tam would be the ship’s sponsor – a role that had, up until that point, been filled by the wife of the man for whom the ship was named. ‘I think it is fitting the the celebration of Sally’s legacy as a pioneering space explorer and a role model includes an acknowledgment of who she really was and what she cared about,’ said Tam. The R/V Sally Ride, commissioned in 2016, is the first navy research ship named for a woman. Her legacy lives on in the scientific curiosity sparked in the girls and boys she continues to inspire, the ship that bears her name, and a spot on the moon named after her by NASA.”

Military readers may find fascinating nuggets of history in the essays about Sylvia Earle, Mary McLeod Bethune, Florence Nightingale, Eleanor Roosevelt, and Mary Edwards Walker. Chelsea writes this about Walker:

“…Dr. Mary Edwards Walker, the only woman in her medical school class at Syracuse Medical College in 1855. She was a practicing physician when the Civil War broke out. She desperately wanted to enlist in the Union Army as a surgeon but wasn’t allowed to because she was a woman. Initially she was called a nurse, since women generally weren’t considered doctors. Because women were not allowed to enlist, Mary had to volunteer, working for free at a temporary hospital, first in Washington and then in Virginia, where she traveled to Union field hospitals across the commonwealth … When her medical credentials were finally accepted she moved to Tennessee and became a War Department surgeon – a paid position that was the equivalent of a lieutenant in status.”

“When I think of Sylvia’s work, I am reminded how important it is for all of us to peruse and consider what we want to leave to the generations who come after us –– how they’ll honor the past, imagine the future, and give gifts to those who will live out their lives long after we’re gone. That’s exactly what Sylvia’s life as a scientist, an engineer, a teacher, and an explorer should inspire all of us to do: we must preserve our oceans for the future.”

Last year, this book generated controversy because of the women who were not included. For example, there is an unfortunate dearth of women who have served in or with the military. Surely, the authors could have included a “protectors” section filled with inspiring women who served in uniform.

Despite the intriguing photo on the cover, there is little focus on the women who served on the Homefront during the Second World War. In fact, there’s no explanation of the colorized photo of the women firefighters at the Pearl Harbor Naval Shipyard.

Yet, considering the general lack of attention toward the achievements of women in American and world history for many generations, it is refreshing to see a book of this scope. Women continue to knock on the door, push through the glass ceiling, and demand equality.

“The Book of Gutsy Women” illustrates the strengths of women throughout history, often in the face of sexism, misogyny, harassment, and patriarchy. It highlights the facts of women’s history and showcases women’s contributions to creating a better world now and in the future.