Review by Bill DoughtyThis 900-plus-page book took some time to read. Not just because of the length, but also because it was so damn good. Parts demand to be read and reread.

Ian W. Toll completes his “unexpected” trilogy of the history of World War II in the Pacific in “Twilight of the Gods: War in the Pacific, 1944-1945” (W.W. Norton, 2020), a book that brings in new archived material, information, and reports, including from former Imperial Japan about their “demented” war and efforts to brainwash their people.

Standouts in the book are the depiction of the kamikaze fighters in the skies and also on land and at sea; the details of fighting in the Philippines, Iwo Jima, and Okinawa; and the description of military leaders, both American and Japanese.

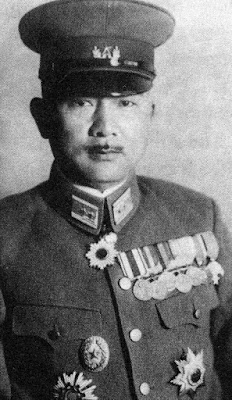

Here’s his description of Lt. Gen. Kuribayashi, for example:

“In June 1944, two days before U.S. forces had stormed ashore on Saipan, a new commanding general flew into Iwo Jima. Lieutenant General Tadamichi Kuribayashi was a stout man of medium height, aged fifty-three, with a small, trim mustache. He was one of the star officers of the Japanese army, having distinguished himself in staff jobs and in the field. While serving as military attaché in Washington in 1928-1929, he had mastered English and traveled widely through the United States. He had commanded a cavalry regiment at Nomonhan, Manchuria, during the undeclared war between Japan and Russia in 1938-1939. After 1941, he had served as chief of staff of the South China Expeditionary Force in Canton. More recently, he had transferred to Tokyo to command the Imperial Guard, a prestigious posting that brought him into direct contact with the emperor. His new command gave him dominion over the 109th Division and the Ogasawara Army Corps, which included all garrison forces in the Bonin Islands. Upon his departure from Tokyo, Prime Minister Hideki Tojo had instructed Kuribayashi to ‘do something similar to what was done in Attu.’ That amounted to a suicide order: that Kuribayashi must defend the island to the last man.”

That’s another standout theme in this book: the role of the press, propaganda, and psychological operations.

“Twilight” illuminates the importance of truth-telling and the role of the press. There is a thin line between freedom of the press, for example, and fear mongering, censorship, and aiding the enemy. What is in the public interest? How important is national morale? Should the president be concerned about not inciting panic? Will an informed public be more supportive if people are told the truth?

Admiral E. J. King, Chief of Naval Operations, at first wary of the press, quickly saw the value of conducting in-person secret press briefings. He met with reporters over beer and canapés at Nelie Bull’s House to provide context to some of FDR’s, his, and Nimitz’s decisions. In return, he “acquired a fund of goodwill in the Washington press corps.”

That goodwill helped steer Congress away from military unification, in effect putting all military resources under the Army and risking the creation of an overly powerful Pentagon.

For understandable operational security reasons, Admiral Nimitz and his team in Hawaii were low-key and hesitant to provide information and details of the war.

|

| Gen. Douglas MacArthur |

Meanwhile, across the Pacific, Gen. Douglas MacArthur openly attracted “carefully managed” press coverage, especially stories that matched his version of the facts. “The thicker they laid on the praise and adulation, the more they would be rewarded with exclusive stories and other desirable privileges” by MacArthur’s censors.

“More than any other American military leader of the war, MacArthur understood the importance of visual imagery. He paid diligent attention to the details of his wardrobe and accessories, which cynics called his ‘props’ –– his battered Philippine field marshal’s ‘pushdown’ cap, his well-worn leather flight jacket, his aviator sunglasses, and his corn-cob pipes, which tended to grow larger over time. During his first days in Australia, he had experimented with an ornate carved walking stick, but discarded it after someone remarked that it made him look older. He was sensitive about his expanding bald spot, and when it was necessary to be photographed without his hat, he took a private moment to comb his hair across the top of his head, leaving a perfectly straight part about two inches above his right ear –– a deftly executed version of the coiffure known as a ‘combover.”

Photography was also censored, and “most published wartime photographs of MacArthur were taken at a low camera angle, making him appear taller than he was,” Toll writes. His press office was accused of “abusing its powers of wartime censorship to indulge MacArthur’s personal vanity.” Toll writes, “MacArthur was a serial confabulator.” The general’s “moonshining” would be called “gaslighting” today.

Toll convincingly shows how Admiral “Bull” Halsey fell for a Japanese ploy to lure him north during the Battle of Leyte Gulf. This, combined with Halsey failure to dodge a typhoon “when there was still time,” paints him with a different brush then the largely media-created image he had during the war. “But until his death in 1959, the proud old fleet admiral fought a losing rearguard action against the hardening judgment of history.”

By contrast, Admiral Mitscher, who led Task Force 58, comes across as a winner, a leader with grace and compassion. Admiral Spruance is depicted as a bit quirky but also a man of great humility and quiet wisdom. Admiral King, Toll contends, was a careful listener who “considered counter-arguments in good faith.” Of course, Nimitz epitomizes humble but strong leadership.

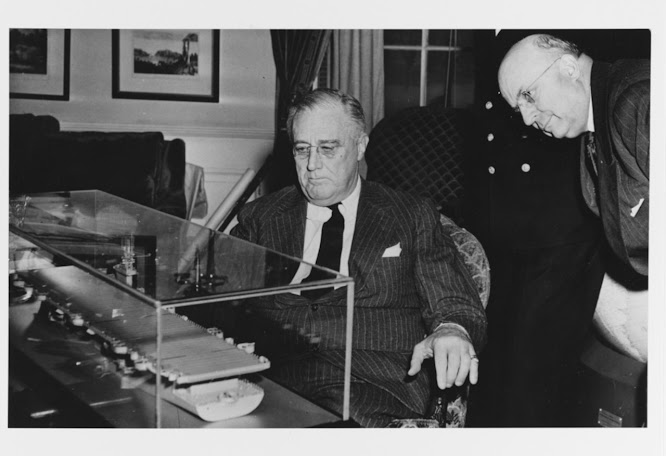

|

| Navy leaders King, Forrestal, and Nimitz |

Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, strongly supported both the Navy and Marine Corps, and saw the value of the American press in communicating with the public to garner support for the war effort. With helmet on, he stepped onto the sands of Iwo Jima and witnessed the raising of the American flag on Mt. Suribachi by United States Marines. He told General “Howlin Mad” Smith: “‘Holland, the raising of the flag on Suribachi means a Marine Corps for the next 500 years.’”

“The Navy secretary had been pushing for more fulsome publicity in Nimitz’s theater. He had taken a direct hand in streamlining censorship functions, and had pressured the admirals to guarantee overnight transmission of press copy and photographs to newsrooms in the United States. During his current tour of the Pacific, Forrestal had often reminded the navy and marine brass that an epochal political struggle lay ahead over the organization and unification of the armed services, and the postwar status of the Marine Corps was not yet decided. The “500 years” remark this had a contemporary context and subtext: Forrestal meant that the stirring image would strengthen the corps’ claim to an autonomous role in the postwar defense establishment.”

“A second and more famous flag-raising (top photo) occurred three hours later, when a subsequent patrol of the 28th Marines carried a larger ‘replacement’ flag to the summit of Mt. Suribachi. Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal was on hand to record the scene.”

Forrestal, with Admiral Leahy, would play a key role in streamlining eventual surrender and acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration by the proud but divided Imperial Japanese military government.

Meantime, strong Navy and Marine Corps leadership led to victories across and up the Pacific, and Toll takes readers on a gripping journey in the last year of the war. He provides maps of locations, operations and actions, including: Ulithi Atoll, Surigao Strait, Leyte, Marianas, Operation Iceberg, Operational Olympic, Third Fleet Operations Against Japan, and Yamato’s Last Sortie, among others.

This is Toll’s “you-are-there” quality of writing as he describes the destruction of the hapless IJN battleship Yamato (pictured above, photo courtesy NHHC):

“In a second wave of attacks, beginning about forty minutes after the first, the Yamato took five or six more torpedo hits on her port side, and at least one to starboard. Another exploded against her stern, destroying her rudder post and depriving her of steering. SB2C dive-bombers rained heavy armor-piercing shells down along her topside works, while warms of low-flying Hellcats and Corsairs strafed her remaining antiaircraft batteries. Yoshida recalled ‘incessant explosions, blinding flashes of light, thunderous noises, and crushing weights of blast pressure.’ The destroyers Asashimo and Kasumi were badly mauled, and would either sink or be scuttled. The immobilized Yahagi caught four more torpedoes and seven or eight more bombs. Captain Hara, looking fore and aft, judged that his ship was nearly finished. Whitewater towers erupted as torpedoes exploded against the hull. Bomb blasts ejected debris and bodies into the air. Rivets began popping our of the steel deck plates and the bridge began pulsating under his feet. ‘Our dying ship quaked with the detonations,’ wrote Hara. ‘The explosions finally stopped but the list continued as waves washed blood pools from the deck and dismembered bodies fell rolling into the sea.’”

Japanese mother and child photographed amid the ruins of Tokyo, Japan, September 1945, by visiting crewmen of USS THORN (DD-647), NHHC.

The loss of life in a death cult mentality of extreme nationalism and misplaced patriotism comes across as a crushing tragedy, particularly at the end of the war in the Battle of Okinawa, fire bombing of Tokyo, and world-changing atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The war was prolonged by Japanese “army hotheads” –– hardliners who attempted a last-minute coup. They spread rumors that Emperor Hirohito’s recorded surrender announcement was “faked.” Senior military leaders “wanted peace, but they could not yet face up to the stark reality of their total defeat.”

In a last-ditch effort to stave off defeat, Imperial Japan tried to make a deal with the Soviet Union, but Stalin opportunistically declared war on Japan, attacking Japan-occupied Manchuria (pictured at left) and northern Korea, then setting sights on Japan’s large northern island: “If the Japanese surrender had been delayed by even a few weeks, Japan’s northern island might have passed [like half of Germany] forty-five years on the other side of the Iron Curtain.”

Another standout insight: Imperial Japan’s propaganda campaign to brainwash its own people was hollow because it was based on lies about the American military; American propaganda, on the other hand, aimed at Japanese citizens in the form of radio broadcasts and leaflets over mainland Japan, was heroic in attempting to achieve a peaceful surrender.

“The surprise and relief felt by the Japanese, upon learning that their former enemies were largely decent and honorable, was accompanied by another sensation. With a sudden rush, ordinary Japanese understood how thoroughly deceived that had been by their own leaders. The propaganda was still ringing in their ears –– they could hardly forget it –– but it all seemed demented in retrospect. The Potsdam Declaration had insisted: ‘There must be eliminated for all time the authority and influence of those who have deceived and misled the people of Japan into embarking on world conquest,’ and the country must be rid of ‘irresponsible militarism.’ The Japanese people would fulfill that condition on their own, regardless of the policies of their postwar government. The wartime military leadership was held in widespread contempt. These attitudes had been prevalent even before the surrender, though never uttered publicly for fear of repression. Now they came to the surface –– potent, instinctive, deeply held hatred of war, and for those who had plunged Japan into it.”

For American warfighters, the end of the war was a time for celebration and healing but also frustration. Most service members had to wait for weeks and months before being able to return from overseas. “Bing Crosby’s ballad ‘I’ll Be Home for Christmas’ played in heavy rotation on the Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS) –– but now, more than ever before, the melancholy refrain seemed to mock their dilemma: ‘if only in my dreams.’”

Toll’s War in the Pacific trilogy deserves to be on any WWII historian’s bookshelf. It is indeed a masterpiece of harrowing history, well told.

ADM Spruance and VADM Wilkinson walk in Yokosuka, Japan, Oct. 1945.