Review by Bill Doughty

Review by Bill DoughtyWhen it comes to strange and wonderful places or things in our Universe, it's not about the who or what or where or when or even why; according to authors of "Atlas Obscura," it's the "how"––specifically, how we choose to see our world and everything around us.

The opportunities to discover, see and catalogue new wonders are "infinite," according to Dylan Thuras, "if you're willing to sort of slow down, look around, listen and start asking questions."

Thuras, Joshua Foer and Ella Morton bring us this book packed with question-asking strangeness, subtitled a Freakonomics-esque "An Explorer's Guide to the World's Hidden Wonders" (2016, Workman Publishing).

|

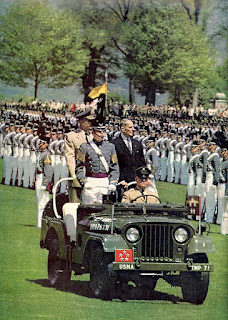

| Mary Roach enjoys a different perspective including "Atlas" |

Once a person chooses to see the world differently, they can discover places in their own neighborhood––or aboard their ship––or in places admittedly farther afield that are strangely fascinating.

That's the approach the authors take as they journey into the world in what Mary Roach, author of "Gulp" and "Grunt," describes as “a joyful antidote to the creeping suspicion that travel these days is little more than a homogenized corporate shopping opportunity. Here are hundreds of surprising, perplexing, mind-blowing, inspiring reasons to travel a day longer and farther off the path."

Some places and things in this book to see in a new light: "Cargo Cults of Tanna" in Vanuatu archipelago, "Slab City" and the "East Jesus" community on a former U.S. Marine Corps training base near Niland, California, "Yamamoto's Bomber" wreckage still in the jungle north of Buin, Papua New Guinea, "Ghost Fleet of Truck Lagoon" in Chuuk, and the not-to-be-missed (?) "Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum" in Pyongyang (mural at right).

Some places and things in this book to see in a new light: "Cargo Cults of Tanna" in Vanuatu archipelago, "Slab City" and the "East Jesus" community on a former U.S. Marine Corps training base near Niland, California, "Yamamoto's Bomber" wreckage still in the jungle north of Buin, Papua New Guinea, "Ghost Fleet of Truck Lagoon" in Chuuk, and the not-to-be-missed (?) "Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum" in Pyongyang (mural at right).Website Wonders

The wonders of the "Atlas Obscura" spring from the popular website of the same name.

Foer and Thuras are cofounders of the Atlas Obscura phenomenon, who see there work as "never complete" and who are always ready to credit legions of fans who provide tips, photos and edits as "co-authors."

In the introduction to the new book they proclaim, "Though Atlas Obscura may have the trappings of a travel guide, it is in truth something else. The site, and this book, are a kind of wunderkammer of places, a cabinet of curiosities that is meant to inspire wanderlust as much as wanderlust."

Here are just a few of the wonders to be found on their website, on the internationally themed #navalhistory section:

John Paul Jones tomb:

"Today, Jones rests in a extravagant sarcophagus below the chapel of the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland. The incredible coffin is covered in sculpted barnacles and is held up by legs in the shape of stylized dolphins. The whole thing is sculpted out of a black and white marble that makes it look as though it has been weathered by untold ages beneath the waves."

NOAA's Discovery of USS Conestoga:

"In September 2014, a team from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration was on an expedition in the Greater Farallones National Marine Sanctuary, looking for shipwrecks, when they found the wreck ... a seagoing tugboat. It had a metal hull, and though the upper deck had collapsed, the boilers, the anchor and the engine were all still there. They determined that it had been powered by coal, which dated it to the late 19th century or early 20th ... When the Conestoga disappeared, it was the last U.S. Navy ship to be lost, without explanation, during peacetime. Planes and ships were sent out to find it, in the largest air and sea search in Navy history until the hunt for Amelia Earhardt. But for almost 100 years, it remained lost."

USS Constitution

"Commissioned by the first US president, George Washington, the USS Constitution is probably most famous for defeating numerous British warships in the War of 1812. It was during this war, in the battle against the HMS Guerriere, the ship earned the nickname “Old Ironsides,” when her crew noticed shots from the British ship simply bounced off. The USS Constitution is America's Ship of State ... Today the ship is berthed neatly at Pier 1 of the former Charlestown Navy Yard, at the end of the Freedom Trail in Boston, where she stands the oldest commissioned and fully functioning warship in the United States. The wooden-hulled, 3-mast heavy frigate of the US Navy was launched in 1797 ... Today, the ship keeps a crew of 60 officers and sailors to aid in its mission to promote the understanding of the US Navy's role in war and peace, as part of the Naval History & Heritage Command. The crew are all active-duty Navy sailors––an honorable special duty assignment ... Until current restoration work is complete, the ship is in Dry Dock. The USS Constitution is still open to the public on a first-come, first-serve basis during their operating hours."

Mare Island Cemetery

"Hidden away on Mare Island in Vallejo is the Bay Area's oldest Naval cemetery, the final resting place of sailors and soldiers and loved ones--and one convicted killer ... Burials began at this hillside cemetery in 1856 and continued until 1921. Although it's not noted for big-name interments, there are some memorable stories among the headstones. Among the approximately 900 buried here are the daughter of Francis Scott Key, murderess Lucy Lawson, and six Russian sailors who were laid to rest near the middle during the Civil War era."

Treasure Island Naval History Mural

"Within the lobby of Treasure Island’s former administration building of the 1939 World’s Fair is a mural that stretches 251 feet long and 26 feet high. Designed by New York artist Lowell Nesbitt and executed by a team of a dozen Bay Area painters, the enormous artwork depicts naval history in the Pacific since 1813, featuring a total of eleven Navy and Marine Corps events. The mural was completed in 1976 to align with the opening of the Navy-Marine Corps Museum, which included artifacts from Treasure Island’s World's Fair, Pan Am Clipper flights and American military operations in the Pacific ... Today, the building is occupied by the Treasure Island Development Authority. The museum artifacts have come and gone, but the impressive mural continues to glow on the lobby’s East wall."

Granted, there is not much from the Navy-Marine Corps team in Atlas Obscura, especially in the new book. But, before you shrug: For anyone interested in "how" to look at world differently, this book––and of course the Atlas Obscura website––is a treasure trove of weirdness and enlightenment.

Mary Roach calls this "...Bestest travel guide ever.”