Review by Bill Doughty

The long arc of history bends toward justice, as Martin Luther King observed, but the arc is jagged –– two steps forward, one step backward. Yet with age, education, and knowledge, often comes wisdom and a clear perspective of the way forward to a “more perfect union.”

|

Some key insights Rather shares: We can find strength through kindness and diversity. We can be patriotic through empathy and inclusion. We can be responsible citizens by caring for the environment, getting an education, and finding ways to serve. (At right: Service – Sailors aboard USNS Comfort (T-AH 20) evaluate a Guatemalan infant, June 27, 2007, during a humanitarian deployment, DVIDS).

And we can achieve greatness as individuals and as a nation by repairing our faults, to paraphrase de Tocqueville (who the author quotes in his epigraph). Another quote Rather shares is from George Washington, who “in his famous Farewell Address, warned future generations ‘to guard against the impostures of pretended patriotism.’”

What does it mean to love America and to be committed to moving forward along the arc toward justice? “It is important not to confuse patriotism with nationalism,” he writes. “Patriotism –– active, constructive patriotism –– takes work. It takes knowledge, engagement with those who are different from you, and fairness in law and opportunity. It takes coming together for good causes.”

Here’s a found haiku in “What Unites Us”:

We are a nation

not only of dreamers, but

also of fixers

“We have looked at our land and people, and said, time and again, this is not good enough; we can do better,” he writes.

|

| Houston, circa 1935 |

As a child, Rather was an eyewitness to the Second World War on the Homefront. As a young man he enlisted in the Marine Corps. But he regretted having to be forced to leave boot camp after suffering health issues from having contracted rheumatic fever in childhood

Rather found another way to serve in war zones; he became a renowned reporter, following in the footsteps of his hero Edward R. Murrow. Now, at 89 years old, Rather reflects on the American history he has seen and experienced.

Rather shares anecdotes about people he knew on the Homefront after the traumas of the Great Depression in the 1930s and World War II in the early-to-mid 40s, and he explains how the war mobilized and united the nation, especially after Pearl Harbor.

“It is perhaps not surprising that Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan looked at a nation so traumatized and felt they could defeat us. Of course, history turned out differently. The same generation that had been driven to such depths in the 1930s rose up to push back the forces of totalitarianism in a two-ocean global war in the 1940s. Perhaps those authoritarians, who felt no empathy for their own people or those they conquered, underestimated the strength of our empathy. Empathy builds community. Communities strengthen a country and its resolve and will to fight back. We were never as unified in national purpose as we were in those days. What had weakened us had also made us stronger.”

WWII and Korea (“the forgotten war”), he says, were turning points for our nation.

“We have never fully regained the confidence we felt at the end of World War II, or the unity. Korea led to a long and arduous path of questioning our place in the world. We did not always win wars, as we would soon have to relearn in Vietnam. We could not take our destiny for granted, as we began to realize under the shadow of the Cold War. There were deep ruptures and injustices within our nation, as we would see when the national spotlight shifted from the fissures of McCarthyism to the difficult struggle for civil rights.”

|

| Truman integrated the military in 1948 |

“Indeed, this sweep of empathy continued after the war. One of the best foreign policy efforts in American history was to help rebuild Europe and Japan. Our enemies became our friends through acknowledgment of the common bonds of humanity. The postwar world order was built on that foundation. And when the GIs returned home, we treated them empathetically as well. The Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, more commonly known as the GI Bill, was one of the greatest pieces of social legislation in our nation’s history. Among other benefits, the GI Bill ensured that servicemen’s tuitions to college or technical school were fully paid. Empathy makes for wise foreign and domestic policy.”

|

| Nixon is interviewed by Rather in the White House, Jan. 2, 1972. |

Reflecting on the situation in the early 70s, after Nixon resigned in the face of impeachment and Navy veteran Vice President Gerald Ford assumed office, Rather writes, “The steadiness of the nation contrasted sharply with the increasing unsteadiness of President Nixon –– the full measure of which we would not comprehend until after he’d left office.”

“We would do well to study our history,” Rather observes. “For in it lies not only evidence of American greatness, but also the need for humility.”

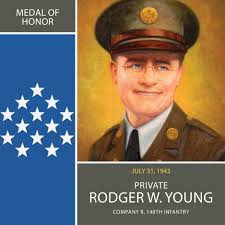

He reminds us of humble American hero Rodger Young, an Army soldier of the Ohio National Guard who fought and died in the Pacific War during the Battle of Munda Point in the Solomon Islands.

In the Battle of Munda Point, Private Young, shot twice by machine gun fire, continued to move forward, firing his rifle and throwing hand grenades to take out an enemy pillbox and save his team. Young was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.

Rather speaks with reverence about visiting cemeteries in Normandy and Honolulu. Rather's/Kirschner’s prose is crisp and unsentimental, but there are still glimmers of poetic insight.

Here is another found haiku in “What Unites Us”:

We live in debt to

those who have served and died, a

debt tallied in blood

Rather reveals truly patriotic American values –– perfect for this challenging time in the wake of a failed coup attempt, in the middle of a deadly pandemic, and as we confront an ongoing threat to our Constitution and democratic republic. Dan Rather provides a strong and hopeful commitment to truth, justice, and accountability in 2021 in this uplifting book. He helps smooth the jagged edges of the long arc of history.

National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, "Punchbowl Crater," Oahu, Hawaii, with Diamond Head in the background.

Panoramic view of the "National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific" at Punchbowl Crater, Oahu, Hawaii, 2 September 1949, four years after the end of World War II. Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, USN, made a speech at the dedication ceremony.

No comments:

Post a Comment