Two western Pacific storms –– one in 1274 CE and another seven years later –– saved Japan from conquest by Kublai Khan and the Mongol Fleet. The invading wooden ships were crushed by typhoons as they neared the Japanese coast. Tens of thousands of Mongols were killed in the invasion attempts.

|

| Raijin |

Superstition reined in Asia, as it did throughout most of the world for centuries. God or gods were the reasons for the actions of nature and of humans.

More than six hundred years after the storms, Imperial Japan, became the invader. Headed by a revered god-like emperor, Nippon’s military invaded its neighbors, including Korea, Mongolia, and Indochina. On December 7, 1941, Imperial Japan attacked U.S. territories, including Pearl Harbor and other bases on Oahu.

But…

The United States Navy, Marine Corps, and Army/Air Force, with help from Allies, used science instead of superstition to win the war in the Pacific in World War II. How they did it is at the heart of “Lethal Tides: Mary Sears and the Marine Scientists Who Helped Win World War II” by Catherine Musemeche (HarperCollins, 2022).

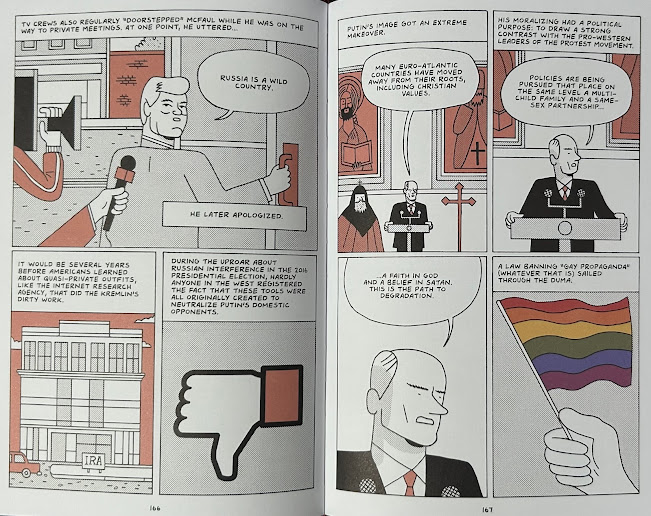

Early in the last century, women had to fight against prejudice, discrimination, and another type of superstition: the belief that if women served aboard ships –– even aboard scientific research vessels –– it could bring about storms, shipwreck, pirates, or other calamities.

“The prohibition of women sailing on oceanographic vessels grew out of ancient taboos that originated in myths and legends, like Homer’s Odyssey, where after the Trojan War, Odysseus sails home with his all-male crew. Although he encounters numerous female characters during his stops along the way, nary a one dares to set foot on his ships. Ships are where men exercise their manly skills like war mongering and fending off monsters while simultaneously battling storms and rogue waves. Allowing women on board would only distract the crew from their duties and incite the wrath of an angry sea, leading to certain misfortune. For hundreds of years sailors clung to these beliefs and preserved the all-male domain at sea even while perpetuating the striking paradox that a female body carved into the bow of a ship would bring good luck on a voyage.”

“But not every woman was willing to adhere to this nonsensical restriction,” Musemeche writes. She presents a brief but good history of women breaking barriers on behalf of science, for greater equality, and to have opportunities for careers, including in the nascent field of oceanography.

|

| Mary Sears |

Other men, though, stuck with old-fashioned views of “a woman’s place.” Senator David I. Walsh, chairman of the Senate Naval Affairs Committee, for example, declared “that to permit women to become members of the armed forces would destroy their femininity and futures as ‘good mothers.’” As a result, the Navy was slow to fully accept help from women who wanted to serve but eventually turned toward actively recruiting women for non-combat roles.

Sears persisted in her work and earned a leadership position at the Hydrographic Office during World War II, where, with other WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service) and scientists, she provided mapping, analysis, and much-needed intelligence, especially helpful to submariners and amphibious assault operations. “Her colleagues realized Sears could be depended on to provide the answers the military needed to wage war in the oceans.”

Though her background was anchored in biology, she and her team provided key and essential information about tides, waves, surf zones, reefs, currents, underwater obstructions, and the composition of shorelines –– analyzing “a fusion of hazards” for the military.

Such information, formulated in Joint Army Navy Intelligence Studies (JANIS) reports, was found to be much needed after the Battle of Tarawa, which revealed flaws in planning. “The resulting lack of preparation manifested on the blood-stained beaches of Tarawa,” Musemeche writes.

|

| Marines wade ashore at Tinian, July-August 1944. (NHHC) |

“As the Pacific Campaign unspooled, getting the troops to shore presented a range of problems, confirming what Sears had said about the Navy’s lack of preparation. They had gone to war knowing very little about the ocean, at least about the offshore challenges of launching amphibious landings. But there was no stopping the action so American forces could rehearse and get better. The march to Japan would not wait.

The Americans had not fought this way or at this pace before. In World War I troops had sailed across the Atlantic into welcoming harbors, docked at piers, and unloaded without enemy resistance. Those operations were easily achieved without oceanographic information. The Allies rarely had such advantages in World War II. Harbors, if they existed at all at island targets, were not welcoming. There were no piers at which to dock. There was nothing simple about dropping marines into boats and tractors bucking in the grasp of heaving waves and sending them over jagged coral reefs, under a barrage of machine-gun fire and artillery shells toward plunging waves. The problem was, there didn’t appear to be any other way to win the war in the Pacific.

The success of the Pacific Campaign mandated capturing one island after another in far-reaching locales, as the military worked its way toward Japan.”

Musemeche tells of a set-back in planning for the assault of Iwo Jima. She writes of the hardship of rationing on the homefront, which impact the ability to do research. And, she shows how the war impacted everyone as the loss of loved ones in the Pacific and in Europe touched the lives of colleagues and friends.

Her description of the action on Palau is heart-pounding and searing. Admiral William H. McRaven endorsed the book: “Magnificently researched, brilliantly written, Lethal Tides is immensely entertaining and reads like an action novel.” (The book is lovingly dedicated, by the way, to Musemeche’s father, QM3 Frank M. Musemeche, who served in WWII.)

|

| USNS Mary Sears (T-AGS-65) at Yokosuka, Japan. (MC2 Travis Bailey) |

Imperial Japan’s military refused to surrender, with many leaders and troops and even some civilians preferring to commit suicide.

The kamikaze pilots who crashed their planes into U.S. Navy ships, were named “divine winds” after the storms that superstition said were brought about by the gods to protect Japan from invasion. It took the science of the atom to finally bring forth a surrender after the President Truman authorized nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz credited Lt. Cmdr. Mary Sears and her team more than once for contributing to successes in the Pacific War.

In 1946, Nimitz issued a postwar commendation crediting her “technical knowledge and administrative skill.” Sears’s use of science, data, and analysis, provided exceptional assistance to warfighters.

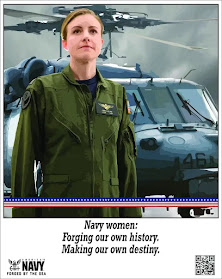

USNS Mary Sears, the first oceanographic survey ship named for a woman, was christened in 2000 by Mary’s younger sister Leila, who herself served as a WAVE in the Navy’s code decryption department.

Packed with under-reported facts, compelling photos, and actual data reports, this is a wonderful book for anyone interested in appreciating the depth of women’s history, the power of science and technology, and the strength of diversity and inclusion. BZ!

Pathfinder-class oceanographic survey ship USNS Mary Sears (T-AGS 65) hosted U.S. Ambassador to Australia Caroline Kennedy during the ship’s scheduled visit to Sydney, Australia, Nov. 8, 2022. Ambassador Kennedy toured USNS Mary Sears and received a Naval Oceanography overview from Commander Jonathan Savage during her time aboard. The visit was Ambassador Kennedy’s first to an oceanographic survey vessel and her first visit to a U.S. Navy ship since taking office as U.S. Ambassador to Australia in July 2022. Kennedy is former U.S. Ambassador to Japan. She is the daughter of Navy hero President John F. Kennedy. (Photo by Lt. Cmdr. Bobby Dixon)