Review by Bill Doughty

Fareed Zakaria takes a global look at the past to predict the future in “Ten Lessons for a Post-Pandemic World" (W.W. Norton & Company, 2020). In fact, Zakaria takes an out-of-this-world look at the impact of disease, pollution, and climate change on human survival:

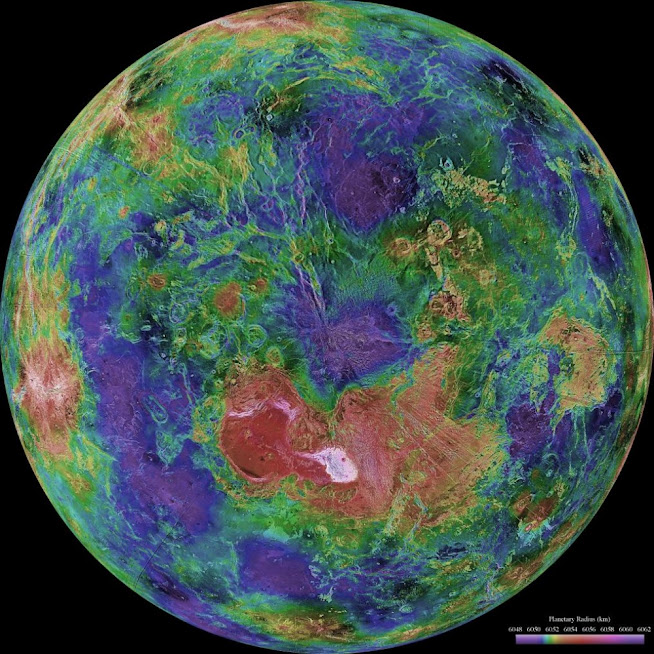

“Climate scientists who warn of the dangers of our current path are unconsciously mirroring Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg’s warnings to us about viruses, back in 1989. Like him, they are urging us to assume that nature is a benign force that has any particular interest in the survival of life on this earth. The climate doesn’t care about us; it is simply an accumulation of chemical reactions that could easily get out of control and destroy the planet and all who live on it. Millions of other planets in other celestial systems may have suffered the same fate. In our own solar neighborhood, NASA’s recent computer modeling suggests that Venus (above) might have been habitable for around 2 billion years, after which a ‘runaway greenhouse gas effect’ led to the scorched and sterile conditions on the Venus of today. We can mitigate the forces that are pushing the earth in a similar direction. If that is not a sound reason for cooperation, then we will not find another.”

Non-cooperation within and between nations can be life-threatening.

Cooperation, on the other hand, can be lifesaving. That’s a chief lesson of the COVID-19 pandemic: telling the truth, marshaling resources, and cooperating together can reduce the number of cases and prevent deaths.

“If people cooperate, they will achieve better outcomes and more durable solutions than they could acting alone,” Zakaria writes, in what sounds a lot like Adm. Mike Mullen’s ‘A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower’ from 2007. Zakaria continues, “If nations can avoid war, their people will lead longer, richer, and more secure lives. If they become intertwined economically, everyone ends up better off.” Updated versions of the U.S. Maritime Strategy continue to note the interconnectedness of nations sharing the same oceans.

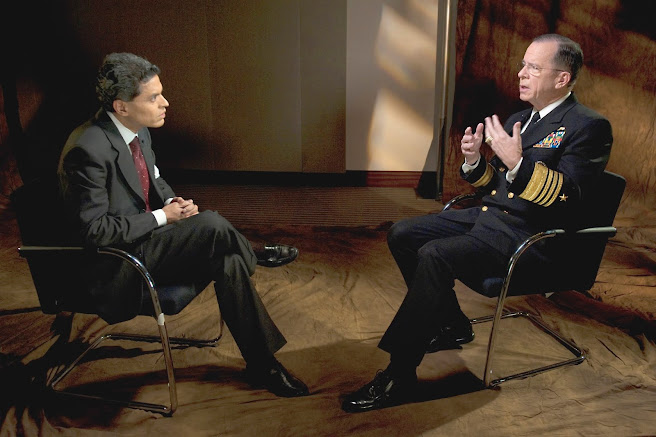

|

| Zakaria interviews then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Mike Mullen in 2010. They discussed, among other topics, a drawdown of troops in Afghanistan. |

Such idealism is not blindfolded. With China’s saber-rattling toward Hong Kong and Taiwan, as well as it’s maritime claims in the South China Sea, the world may be on the verge of another Cold War. Yet Zakaria writes, “Tensions between the United States and China are inevitable. Conflict is not.”

Zakariah shows how a “deeply interconnected” world can prevent wars despite “a real-life butterfly effect,” in which a fluttering butterfly’s –– or bat’s –– wing can supposedly influence the wind and eventually weather patterns on the other side of the world.

“There is a paradoxical feature of pandemics: even though they have come to be named for specific locations, they are decidedly not contained by borders. This has been true for centuries, since the Silk Road caravans and merchant galleys of the medieval world, and especially over the past 150 years since the age of steamships and trains. There was the ‘Russian flu’ of 1889-90, the ‘Spanish flu’ of 1918-19, the ‘Asian flu’ of 1957-58, the ‘Hong Kong flu’ of 1968-69, the ‘Middle East Respiratory Syndrome’ (MERS) of 2012, and now the ‘Wuhan virus’ of 2019-21. By revealing obsession with foreign labels, these names –– even when incorrect as to the origin of the virus –– betray the diseases’ much wider reach. The urge to view a pathogen as coming from abroad is strong, but of course, those diseases have rarely been known by those monikers in the places they’re named for. In Spain, the ‘Spanish flu’ was just the flu.”

Naturally, Zakaria –– a voracious reader –– cites numerous authors and books: William Maxwell’s “They Came Like Swallows,” Katherine Anne Porter’s “Pale Horse, Pale Rider,” Thomas Friedman’s “The Lexus and the Olive Tree,” Francis Fukuyama’s “Political Order and Political Decay,” and Michael Lewis’s “The Fifth Risk,” for example.

Other writers and thinkers he cites include Shakespeare, Clausewitz, Ian McEwan, Yuval Noah Harari, and Doris Kearns Goodwin.

Zakaria quotes Apple CEO Tim Cook, who, like Henry J. Kaiser in the past century, believes that his company’s “greatest contribution to mankind … will be about health.” (Kaiser, who helped shape history in the American West and in World War II, is featured in the most recent Navy Reads post earlier this month.)

It’s in his evaluation of history that Zakaria makes his most insightful conclusions about the importance of international cooperation in the wake of the pandemic –– and toward continued world peace.

“Franklin Roosevelt was assistant secretary of the navy in Woodrow Wilson’s administration and a great admirer of Wilson’s vision of a world ‘made safe for democracy’ He watched that idealism collapse in the years after World War I, leading to an even wider war during his own presidency. But the lesson FDR drew from Wilson’s experiences was to try international cooperation again, this time with America at the center of the new system –– and this time giving the great powers stronger practical incentives to fully commit themselves to the peace. A few months after America entered World War II, when victory was still uncertain and distant, FDR began formulating plans to create international institutions and systems of collective security that made future world wars unlikely. His longtime secretary of state, Cordell Hull, having seen how the trade wars of the 1930s spiraled into hot war, singlemindedly championed a new, international free trade regime. His successors realized this vision in the years after 1945 –– first through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, which evolved into the World Trade Organization.

Roosevelt was known to be an idealist at heart, but his successor, Harry S Truman, had no such reputation. Truman is credited as the hard-nosed realist who dropped the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, created NATO, worked to contain the Soviet Union, and waged war in Korea. But Truman was also a deeply idealistic man, and he too had drunk from the well of Wilsonian internationalism.”

Truman, when asked why he strongly supported the United Nations, would quote from Alfred Lord Tennyson’s poem “Locksley Hall,” a poem which foresaw a world where cooperation reigned and nations formed a federation based on peace, commerce, and “universal law.”

Twice in this book, Zakariah recalls Dwight D. Eisenhower’s visit to the U.S. military cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer in Normandy (above) on the twentieth anniversary of D-Day. In an interview with Walter Cronkite, Eisenhower, who as president had called for abolishing nuclear weapons worldwide and strengthening the UN, spoke to Cronkite about the 9,000 American bodies buried there: “These people gave us a chance, and they bought time for us, so that we can do better than we have before … So every time I come back to these beaches, or any day when I think about that day 20 years ago now, I say once more we must find some way to work to peace, and really to gain an eternal peace for this world.”

“Ten Lessons” advocates for people listening to experts –– and experts listening to people. One lesson is that “what matters is not the quantity of government but the quality.” Another is about the reality of virtuality: “Life is digital.” Still another is recognizing the rise of ultranationalism and that “the world is becoming bipolar” as well as more unequal.

|

U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Larry Hunter, an energy NCO with Headquarters Battalion, Marine Corps Base Hawaii, monitors as a child spins a questionnaire spin wheel during an Earth Day event, Apr. 23, 2019 about the importance of energy conservation, recycling, and protecting the environment. (Sgt. Zachary Orr)

But the most important lesson, one that permeates the whole book, is the importance of the world’s interconnectedness and need for cooperation.

George W. Bush initiated a war on AIDS in Africa. Obama/Biden led the global battle to contain the Ebola virus in Africa. Unfortunately, in early 2020, despite declaring war on COVID-19, the Trump administration failed to acknowledge and confront the threat and provide a centralized plan for testing, tracing, and telling the truth.

“By the middle of 2020, tragically, with the pandemic raging across most of its fifty states –– long after Europe and East Asia contained their outbreaks –– America had no attention for anything or anyone else, except to bash Beijing. The Trump administration is not wrong to critique China’s handing of COVID-19. But coming from such a messenger, the message lands with a thud. A lifelong friend of America, the former Australian prime minister Kevin Rudd wrong in Foreign Affairs of his horror and disappointment over how far America has fallen: ‘Once there was the United States of the Berlin airlift. Now there is the image of the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) crippled by the virus, reports of the administration trying to take exclusive control fo the vaccine being developed in Germany, and federal intervention to stop the commercial sale of personal protective equipment to Canada. The world has been turned on its head.’”

At the beginning of March, 2020, only a few people in the United States had died from COVID-19, but the number of cases was beginning to grow exponentially. By the end of April, just after the United States commemorated the 50th anniversary of Earth Day, there were more than 1 million cases in the U.S. and more than 60,000 deaths –– despite messages from President Trump that everything was under control, the virus would go away, people should take Hydroxychloroquine, and we should try injecting bodies with disinfectants (one year ago this week).

|

A runner pushes through the last 100 meters of a 5K Earth Day Fun Run at Marine Corps Air Ground Combat Center, Twentynine Palms, April 2014. (Cpl. Ali Azimi)

One year later, on Earth Day 2021, there have been nearly 570,000 American deaths. But a coordinated vaccination campaign is working now to reduce cases and fatalities. Unfortunately, the world has suffered 3.1 million deaths due to the novel coronavirus pandemic, and new variants threaten everyone.

“Ten Lessons” presents the stark realities and possibilities ahead; Zakaria warns about the near certainty of another pandemic this century in a connected world. But he also presents an optimistic message about the possibilities ahead if the nations of the world become more educated, more equal, and more committed to cooperation to confront existential threats, including global climate change.

Idealism is not dead. Hope is alive. And the opportunity for lifesaving cooperation is here now despite –– and because of –– the pandemic.

No comments:

Post a Comment