Review by Bill Doughty––

Christmas time in a Hanoi POW camp could be an especially desolate time, but American prisoners had innovative ways to cope. POWs secretly shared memories, stories, “imaginary gifts,” and even Christmas carols secretly through their tap code or other innovative ways to communicate. A pair of bright red socks became a treasured gift. Chewing gum –– among the rare items not confiscated by the guards –– was like a gift from Santa.

Porter Halyburton recounts, “I shared the gum with others, but I managed to keep my piece of gum going for nearly a month until it disintegrated.”

Two years into his imprisonment at Hoa Lo Prison and the “Hanoi Hilton,” Halyburton received his first care package from home. His devoted wife Marty, who at first had no idea he was alive, sent a hand-knitted green sweater. It was Christmas 1969.

“I also got a new ‘towel’ –– actually a large washcloth –– from the Vietnamese, since mine had become threadbare over the years. It was dark green and perfect for a Christmas tree when it was draped into a cone shape and supported by a stick. Silver gum wrappers were used to make tiny balls for the tree as well as a star on the top, and the red socks became Christmas stockings hanging below the tree, which was placed on a platform below the window in the back of the cell. The window could be opened from the outside by the roving guards but, because the walls were double with an airspace between and quite thick, the guards could not see the tree and decorations below the window. We took it down during the day, but it was a magical sight during the night.”

Lt. Cmdr. Porter Alexander Halyburton was captured in 1967 after his F-4B fighter-bomber went down in North Vietnam. He was released, along with other POWs, in February, 1973, shortly after the United States and North Vietnam signed a Peace Agreement on January 27. (The war wouldn’t end for another two years until the fall of Saigon, April 30, 1975).

His “Reflections on Captivity: A Tapestry of stories by a Vietnam War POW” (Naval Institute Press, 2022), is a gift of memories, reflections, and insights. It evokes both tears of sadness and of joy. Readers will cringe at the torture, depravity, and pain endured by prisoners. But there are also stories of pure genius in the ways the POWs overcame cruelty through resilience, innovation, and sheer grit.

Examples of their innovative inventions include making playing cards, dice, and even a slide rule from bread dough and “ink” from cigarette ashes and pig fat. The men memorized names and details of their fellow POWs for future accountability. They developed amazing ways to communicate through their tap code –– sometimes done through coughing, sweeping, or other ways of making sound. And, when vision wasn’t blocked, they communicated through a “deaf-mute” hand signal code. In “Reflections,” Halyburton shows how in descriptive passages and diagrams.

He describes living in the past and future to avoid the present, yet ironically the prisoners who survived captivity did so by facing and overcoming their present circumstances with communication, creativity, mutual support, subtle subversion, and a sense of humor.

I laughed out loud at some of the antics Halyburton describes: tricking the guards with American slang, sing-songing and dancing their roll call. But the most shockingly funny story in the book involves a perverted guard and a duck. Guaranteed to crack you up. “Quack, Quack!”

With a generous sharing of his poetry, private thoughts, and journal entries, Halyburton achieves a deep introspection and personal history that helps us understand the experience of prisoners of war in Vietnam. Readers and lovers of books will be pleased to see his references to authors John M. McGrath, Edgar Allan Poe, Jim and Sybil Stockdale, George Hayward, and Viktor Frankl.

Frankl’s “Man’s Search for Meaning” helped Halyburton put his POW experience and survival into context in its examination of human suffering at the hands of others and what it reveals about ourselves, how we react, and whether we have free will and the freedom to choose. “I realized that our lives were determined more by the choices that we made rather than the circumstances of our captivity."

That, he says, was “the first great lesson” he learned from his captivity.

“I learned a second great lesson from my experience, but it did not come until the very end. As I wrote in my journal, when I walked through the gates of the Hanoi Hilton on February 12, 1973, as we were leaving the prison the had symbolized all the misery and hatred that we had endured over those many years, I turned to face the compound and said, ‘I forgive you.’ I did that because I knew I could not and should not carry that hatred back home with me, back to my family and my life of freedom. I realized during the last few hours of my captivity that although hatred had been useful as part of the armor that had protected me from the influence of my captors, it was no longer needed. Hatred is a poison to the soul, mind, and body, and it has been the source of many of the ills in the world throughout most of our history … One must choose to forgive.”

|

| Reuniting with family, hugging Dabney, in 1973. |

Speaking of which…

In 2022, we’ve seen a thriving democracy –– Ukraine –– under attack by Putin’s Russia, and we wonder if the world can forgive the unforgettable murder, terrorism, and destruction Putin continues to unleash out of pure hate.

Today, Ukraine’s President Zelensky visits the United States to express his thanks to Americans for our defensive military support, in the name of freedom.

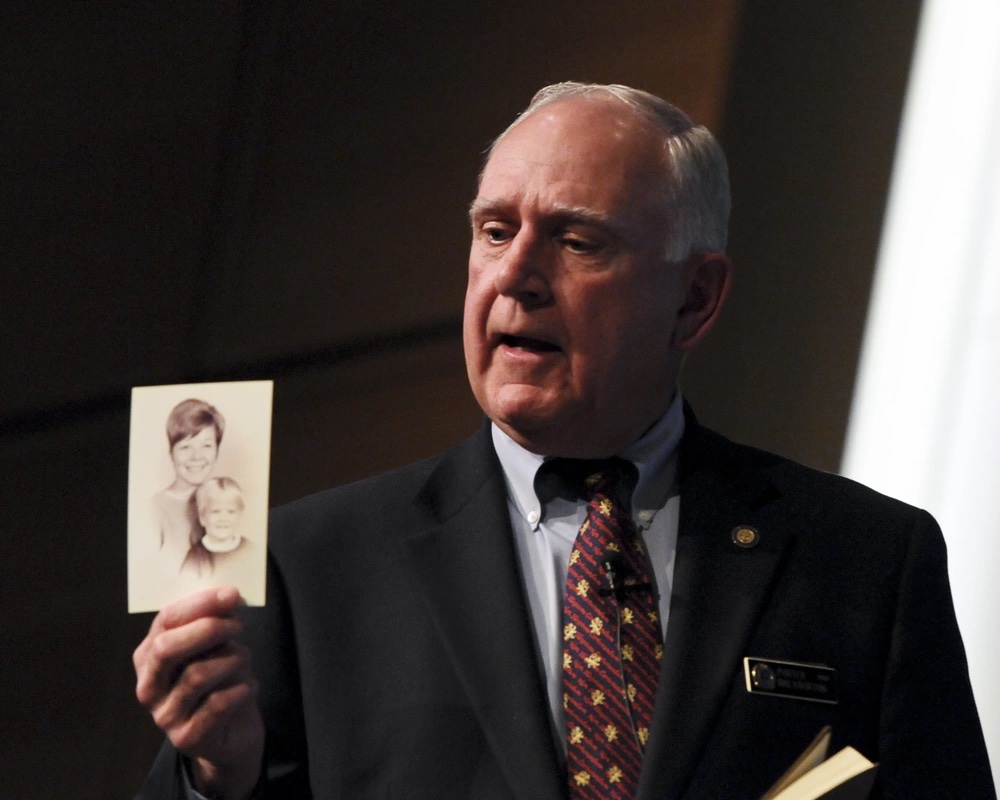

Top photo: U.S. Naval War College Professor Emeritus Porter Halyburton shows a photo of his wife and daughter during a lecture at the Naval War College about his time as a prisoner of war in North Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Halyburton was held captive for seven years in a number of prisons, including the infamous “Heartbreak Hotel” and “Hanoi Hilton.” (MC2 Eric Dietrich)

No comments:

Post a Comment