Review by Bill Doughty––

Combustible racial tension ignited one hundred years ago when a number of whites in Tulsa, Oklahoma, took up arms and threatened to lynch a black teenager. Two thousand whites fought with a group of thirty black men, including World War I veterans, who tried to protect the teen.

The white mob then attacked and burned down the Greenwood district, a black middle class neighborhood known at the time as “Negro Wall Street.”

Dozens of people –– most of them African Americans –– were killed in what was called a riot but is now known as a massacre. Between 150 and 300 people may have died, according to historians. Police joined the white mob in attacking black people in Greenwood.

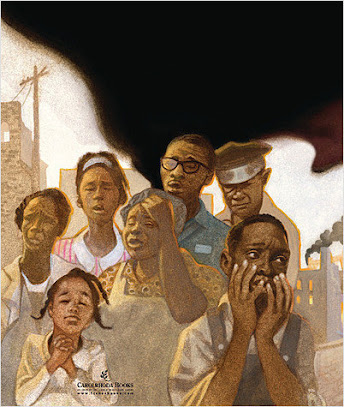

Carole Boston Weatherford (author) and Floyd Cooper (illustrator) capture the tragedy of Greenwood in a new book for young readers. The irony of the title “Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre” (Carolrhoda Books, 2021), is that the disaster of May 31/June 1, 1921, was not spoken about for decades.

Twenty years ago, Oklahoma Gov. Frank Keating signed the Tulsa Race Riot Reconciliation Act into law. But true reconciliation and accountability –– and prevention of similar violence –– cannot be achieved without an honest examination of events, especially massacres (or insurrections). That’s one reason this book by Weatherford and Cooper is so important and timely.

This book offers a short but clear and truthful history of what happened in Tulsa a century ago.

“Unchecked and, in some cases, deputized by the police, the white mob stormed into Greenwood, looting and burning homes and businesses that blacks had saved and sacrificed to build. Threatening to shoot, the mob blocked firefighters from putting out the blazes. African American World War I veterans took up arms to defend their families and property. But they were outnumbered and outgunned. Families fled with only what they could carry.”Some of the veterans were killed, just a day after Memorial Day. The hate-filled white mob destroyed hundreds of businesses and buildings. Thousands of black citizens were relocated to internment camps outside Tulsa.

Weatherford writes, “Black residents had to carry passes to enter the city.” Some stayed to rebuild the community while others left and never returned. It took 75 years before lawmakers launched an investigation into what had happened in 1921.

In an author’s note at the end of the book, Weatherford speaks to the history of the era and what moved her to write about the massacre, one of several against successful African American communities and thousands of murders of blacks after the Civil War and under Jim Crow laws.

“For me, racist backlash hits close to home. One cousin in Tennessee burned to death in his home, a rumored lynching. In the 1920s, whites allegedly burned down a store that belonged to another of my cousins in an all-black village cofounded by my great-great-grandfather during Reconstruction. In my adopted state of North Carolina, another ‘Black Wall Street’ anchored Durham, once a hub of black enterprise. And another race massacre occurred –– in Wilmington in 1898. Thus, family lore and proximity to history led me to the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre.”

Last summer Navy Reads published a post about the Wilmington tragedy of 1898 and the Navy’s unfortunate connection to that massacre. The Wilmington massacre was instigated in part by a white supremacist newspaper publisher who would later become Secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels.

Again, confronting the truth of our past can help us reconcile. The vestiges of systemic hate-filled animus by some whites toward blacks was on full display one year ago when police officers in Minneapolis murdered George Floyd. Gun violence and mass shootings –– as well as other incidents of hate-based violence –– are on the rise in the summer of 2021. Seeing the truth can show us how far we have evolved, how much more we have to do, and where we need to continue to focus efforts toward greater equality, reform, and accountability.

In his illustrator's note, Floyd Cooper shares the story of his grandfather who grew up in Greenwood. Cooper says this about Grandpa Williams’s recollections:

“Everything I knew about this tragedy came from Grandpa; not a single teacher at school ever spoke of it … Now, the same way my grandpa told the story to us, I share it here with you. My grandpa passed away many years ago, but I hope that my art and Carole Boston Weatherford’s words can speak for Grandpa.”

Cooper’s gorgeous art does indeed honor the men, women, and children who were victims of the Tulsa tragedy. He creates emotional tension in the shading, perspective, and colors –– but most of all in the expressions –– of his subjects: women, men, and children. Their expressions speak volumes of truth.

For adults interested in learning more about the unspeakable Greenwood tragedy, I recommend “Riot and Remembrance: The Tulsa Race War and its Legacy” by James S. Hirsh (Houghton Mifflin, 2002) and “Death in a Promised Land: The Tulsa Race Riot of 1921" (Louisiana State University Press, 1982). Both books include many black-and-white images of the awful events of May 31 and June 1, 1921. Each book dives deep into the history of the massacre and helps explain how feelings of entitlement, envy, privilege, and superiority manifested into violence.

No comments:

Post a Comment