Review by Bill Doughty

A failure of imagination by Imperial Japan’s military-dominated government led to the attack on Oahu Dec. 7, 1941 after leaders ignored a warning by wise IJN Vice Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku:

“Yamamoto, who had witnessed America’s economic might during his tour of duty as Japan’s naval attaché in Washington during the early 1920s, had warned Japanese warmongers before Pearl Harbor, ‘Anyone who has seen the factories of Detroit and oil fields of Texas knows that Japan lacks the national power for a naval race with America.’ Like many observers of the U.S. industrial landscape, Yamamoto neglected to mention America’s shipyards, whose products not only overwhelmed the Imperial Navy but also played a major role in the Battle of the Atlantic and the amphibious landings in the Pacific, the Mediterranean, and Normandy. Their production formats and shop floor practices had little in common with Detroit’s vaunted assembly lines that so impressed Yamamoto and eventually historians of industrial mobilization.”

Author Thomas Heinrich writes a self-described “revisionist” history of the way the United States succeeded in the breathtaking buildup that started even before the war in his new book “Warship Builders: An Industrial History of U.S. Naval Shipbuilding, 1922-1945” (Naval Institute Press, 2020). “Naval expansion coincided with a merchant shipbuilding boom after the outbreak of war in Europe” during the 1930s. It peaked in 1943 and 1944.

Heinrich reveals that rather than relying strictly on cookie-cutter rigid designs and “design freezes,” shipbuilders used innovation, flexible specialization, batch formats, disintegrated production, and skilled and agile labor.

|

Then-Under Secretary of the Navy James V. Forrestal with RADM William R. Furlong (right), Commandant of Pearl Harbor Navy Yard, and another officer, meet aboard the capsized hull of USS Oklahoma (BB-37) in the early stages of salvage at Pearl Harbor, 6 September 1942. Courtesy of the Naval Historical Foundation. (NHHC)

Also, shipbuilders and government leaders forged public-private relationships and enforced ethical principles and core values to ensure shipyards produced warships on time. Managerial incompetence was dealt with quickly by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal, and other senior leaders.

That’s what makes this book relevant and interesting: How did they do it?

USS CASABLANCA (CVE-55), right, about to be launched at Henry J. Kaiser's shipyard, Vancouver, Washington, on 5 April 1943. Two of her 49 sister ships are under construction at left. (NHHC)

Heinrich provides tables, charts, figures, maps and illustrations along with extensive notes. He discusses design and construction, contracting methods, procurement, personnel, engineering, specialization, and welding methods, among other topics.

This book will be interesting to business people, and it is invaluable to anyone connected to Navy and civilian shipyards, ship repair facilities, Navy Supply Corps, Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command –– as well as WWII history buffs.

I enjoyed the comparison of American shipyards and shipbuilding methods with those of Great Britain, Germany, and Japan. Heinrich gives a close look at wartime Yokosuka, with its vertically integrated system of five slipways, six dry-docks, shops, foundries, furnaces, and specialty shops.

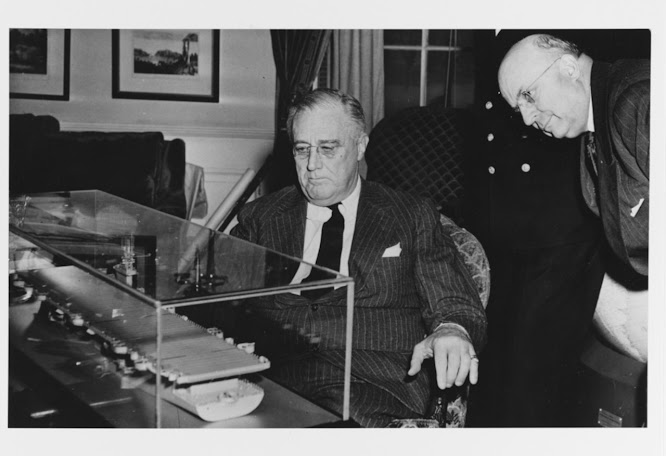

Mr. Henry J. Kaiser, right, presents President Franklin D. Roosevelt with a model of the escort carriers he is constructing at Vancouver, Washington, 18 March 1943. Kaiser built 50 of these CASABLANCA class carriers CVE-55-104 in 1943-44. (NHHC)

Another fascinating insight was the role of the first shipbuilder named in the book (and mentioned throughout), Henry J. Kaiser, described as “a publicity-savvy construction magnate” who had a frosty relationship at best with U.S. Navy brass, who considered him a “showboat.” Nevertheless, Kaiser delivered hundreds of Liberty ships as part of a public-private partnership.

“Private firms delivered the bulk of the fleet that fought in World War II, but their achievements would have been impossible without massive government assistance. Though shipyards that had survived the interwar years constituted major industrial assets, many had suffered underinvestment into physical plant and shop floor equipment that had to be rectified before builders could begin to construct the two-ocean navy. The federal government responded with a variety of initiatives from tax incentives to direct Navy investments, all of which vastly enhanced the private sector’s ability to construct technologically advanced combatants. Recipients of government largesse included not only shipbuilding firms, but also subcontractors responsible for the manufacture of specialty parts in disintegrated batch production formats.”

Yamamoto’s prediction was right. The United States had not only the resources and capabilities but also the will and the unity to persevere. Heinrich writes, “During the war, American builders delivered eight million tons of naval combatants, more than their British, Japanese, and German combatants combined.” Industry, supported by FDR’s government, was an underpinning of American seapower that led to victory, especially in the Pacific.

On Pearl Harbor Remembrance Day 2020, the United States is losing nearly the same number of citizens killed by COVID-19 as American sailors, marines, soldiers, and civilians lost on Dec. 7, 1941.

Unexpected lessons in “Warship Builders” are how we can mobilize to build better, using flexibility and agility; how we can demand honesty, integrity and ethical principles in public-private ventures; and how we can come together as one nation, indivisible, in order to defend against –– and defeat –– any enemy.

Above photo: Less than five months from keel-laying to launching ceremony was the record set by SS Patrick Henry, a Liberty Ship, with time reduced to sixty days in the construction of her sister ships of the Liberty Ship design. On 27 September 1941, SS Patrick Henry, the first U.S. Liberty ship, was launched at Baltimore, Maryland. Numerous other vessels were launched on that day, known as "Liberty Fleet Day.”

Top photo: Sailors in a motor launch rescue a survivor from the water alongside the sunken USS West Virginia (BB-48) during or shortly after the Japanese air raid on Pearl Harbor. USS Tennessee (BB-43) is inboard of the sunken battleship. This is a color-tinted version of Photo # 80-G-19930. Photograph from the Army Signal Corps Collection in the U.S. National Archives.

No comments:

Post a Comment