Review by Bill Doughty––

Slimy charlatans can rise to power and start mass movements with frustrated followers, crazed fanatics and true believers.

In "The True Believer" (Harper & Row, 1951) gifted thinker and writer Eric Hoffer describes how mass movements –– including authoritarianism and totalitarianism –– can get started and perpetuated. Hoffer worked on docks as a longshoreman, but he read and studied voraciously to become a respected American philosopher and educator.

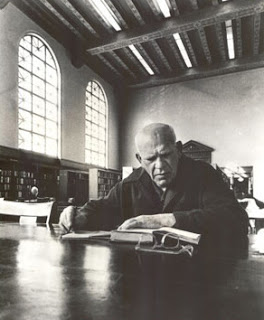

|

| Eric Hoffer, longshoreman philosopher |

Written just six years after World War II, Hoffer's book analyzes how fanaticism can take root and flourish. Examples come from Nazi Germany, Imperial Japan, and Marxist Communism as well as other movements that prey on frustrated and disenfranchised people who feel victimized and in need of something to believe in.

Hoffer explains his use of the word "frustrated" to mean those who feel their lives are spoiled and wasted –– in need of another group to hate, blame and attack.

"That the relation between grievance and hatred is not simple and direct is also seen from the fact that the released hatred is not always directed against those who wronged us. Often, when we are wronged by one person, we turn our hatred on a wholly unrelated person or group. Russians, bullied by Stalin’s secret police, are easily inflamed against 'capitalist warmongers;' Germans, aggrieved by the Versailles treaty, avenged themselves by exterminating Jews; Zulus, oppressed by Boers, butcher Hindus; white trash, exploited by Dixiecrats, lynch Blacks [see my recent post on the Wilmington coup of 1898, the year of Hoffer's birth, coincidentally]. Self-contempt produces in man 'the most unjust and criminal passions imaginable, for he conceives a mortal hatred against that truth which blames him and convinces him of his faults.'" [quoting Blaise Pascal]

According to the editors of Time, who republished Hoffer's book in 1963, "The True Believer" was on President Eisenhower's reading list, and Ike heartily recommended it to others. Hoffer was born in 1898 and died a few months after being awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Reagan.

The book examines not only the rise of charlatans and fanatics but also the acquiescence of a passive public that can allow that rise to occur. Hoffer contends that "true believer" mass movements are not likely to originate in free and healthy democracies. Also fanatics are not apt to come from within an ordered and structured military, although one could argue that's exactly what happened in Japan at the turn of the 20th century and through World War II.

True believers are blind to reason. Faith in their cause requires a rejection of verifiable data and facts. True faith, he says, is suspension of belief in reality –– not faith to move mountains but unyielding belief there are no mountains even when there are.

"A peculiar side of credulity is that it is often joined with a proneness to imposture," Hoffer writes. "The association of believing and lying is not characteristic solely of children. The inability or unwillingness to see things as they are promotes both gullibility and charlatanism."

Fanatics trust their hearts, not their minds; they put their feelings over rational thinking. "They ask to be deceived," he writes in chapter 13. They can see symbols of the past as sacred and unchangeable. "Preoccupation with the past" stems from "a desire to demonstrate the legitimacy of the movement."

"The followers of a mass movement see themselves on the march with drums beating and colors flying. They are participators in a soul-stirring drama played to a vast audience—generations gone and generations yet to come."

True believers and fanatics will be "ready to die for a button, a flag, a word, an opinion, a myth," a ribbon and a greater purpose.

And, if they are willing to die for a cause, they will be willing to kill for a cause. In the case of some mass movements, that means killing innocent civilians.

Hoffer writes, "Hitler dressed up 80 million Germans in costumes and made them perform in a grandiose, heroic and bloody opera." Hitler's henchman Rudolf Hess reportedly told new Nazi Party members in 1934, "Do not seek Adolf Hitler with your brains; all of you will find him with the strength of your hearts."

History shows that charlatan leaders of mass movements are often hateful, paranoid and amoral, if not immoral. Fanatic followers are easily swayed.

"The fanatic is perpetually incomplete and insecure. He cannot generate self-assurance out of his individual resources—out of his rejected self— but finds it only by clinging passionately to whatever support he happens to embrace. This passionate attachment is the essence of his blind devotion and religiosity, and he sees in it the source of all virtue and strength. Though his single-minded dedication is a holding on for dear life, he easily sees himself as the supporter and defender of the holy cause to which he clings. And he is ready to sacrifice his life to demonstrate to himself and others that such indeed is his role. He sacrifices his life to prove his worth. It goes without saying that the fanatic is convinced that the cause he holds onto is monolithic and eternal—a rock of ages. Still, his sense of security is derived from his passionate attachment and not from the excellence of his cause. The fanatic is not really a stickler to principle. He embraces a cause not primarily because of its justness and holiness but because of his desperate need for something to hold on to. Often, indeed, it is his need for passionate attachment which turns every cause he embraces into a holy cause. The fanatic cannot be weaned away from his cause by an appeal to his reason or moral sense. He fears compromise and cannot be persuaded to qualify the certitude and righteousness of his holy cause. But he finds no difficulty in swinging suddenly and wildly from one holy cause to another. He cannot be convinced but only converted. His passionate attachment is more vital than the quality of the cause to which he is attached."

|

| Hoffer at San Francisco Public Library |

The opposite of a fanatic, Hoffer contends, is a "gentle cynic." Justice, open-mindedness and unity –– not retaliation –– can counter hate and division. Sounding like Sun-Tzu, he writes: "To wrong those we hate is to add fuel to our hatred. Conversely, to treat an enemy with magnanimity is to blunt our hatred for him."

Hoffer gives examples of good and "practical men of action" –– leaders such as Lincoln, Gandhi and Churchill –– to counter fanatics. Moral integrity, he says, is not a monopoly of true believers; freedom is worth fighting for and defending. Authoritarian mass movements rely on the passivity of a weak electorate or complacency of a lazy citizenry.

"The first glimpse of the face of anarchy frightens them out of their wits. Not so the fanatic. Chaos is his element ... He shoves aside the frightened men of words, if they are still around, though he continues to extol their doctrines and mouth their slogans. He alone know that innermost cravings of the masses in action... Posterity is king; and woe to those, inside and outside the movement, who hug and hang on to the present."

Good leaders can create positive, creative movements with good, informed people. "The self-confidence of these rare leaders is derived from and blended with their faith in humanity," Hoffer writes, "for they know that no one can be honorable unless he honors mankind."

This is a recommended Navy Reads choice for those interested in defending the Constitution, preventing the rise of fascism/totalitarianism, and in developing good leadership. It's also a good companion to works by Hanna Arendt, Mary Wollstonecraft, Martin Niemöller, Bernard-Henri Lévy, and Madeleine Albright.

Unlike fake charlatans and fanatics, good and honorable leaders "are not tempted to use the slime of frustrated souls as mortar in the building of a new world."

No comments:

Post a Comment