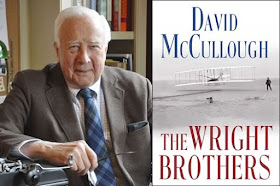

When naval aviator and U.S. astronaut Neil Armstrong became the first man to step onto the moon he brought a physical piece of the Wright Brothers legacy with him. What the fellow Ohioan carried with him is revealed in David McCullough's latest work, "The Wright Brothers" (Simon & Schuster, 2015).

McCullough, the author of "1776," "Truman" and "John Adams," explains how and why Wilbur and Orville were successful in inventing the airplane and demonstrating the first human-operated, powered and sustained flight of a heavier-than-air machine in 1903.

The brothers faced family ravages of typhoid and tuberculosis, swarms of "demon mosquitoes," oppressive heat and plenty of crashes before and after their first flight. Later, another challenge was just getting the scientific community, media and nation to take them seriously.

How they dealt with challenges and setbacks was key to their success.

|

| Wilbur and Orville Wright at home in Dayton, Ohio, 1909. |

The brothers' high school teacher noted "their patient persistence, their calm faith in ultimate success, their mutual consideration of each other."

Books in the Wright family collection included ecclesiastical works alongside works by Robert Ingersoll, who had an apparently significant influence on the brothers, according to McCullough.

"There could be found the works of Dickens, Washington Irving, Hawthorne, Mark Twain, a complete set of the works of Sir Walter Scott, the poems of Virgil, Plutarch's 'Lives,' Milton's 'Paradise Lost,' Boswell's 'Life of Johnson,' Gibbon's 'Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,' and Thucydides. There were books on natural history, American history, a six-volume history of France, travel, the 'Instructive Speller,' Darwin's 'On the Origin of Species,' plus two full sets of encyclopedias."Wilbur was interested in history and science, especially birds, equilibrium and the study of wind.

McCullough's butterscotch voice comes through the narrative as if the reader is listening to a Ken Burns documentary. McCullough's descriptive powers, so strong in all his work, are put to good effect here. For example, here is the author's description of the Outer Banks of Kitty Hawk, North Carolina:

"The previous winter on the Banks had been especially severe, one continuing succession of storms, the brothers were told, the rain coming down in such torrents as to make a lake that reached for miles near their camp. Ninety-mile-an-hour winds had lifted their building from its foundation and set it down several feet closer to the ocean. Mosquitoes were said to have been so thick they turned day into night, the lightning so terrible it turned night into day. But the winds had also sculpted the sand hills into the best shape for gliding the brothers had seen, and the September days now were so glorious, so ideal, that instead of turning at once to setting up camp, they put the glider from the year before in shape and spent what Wilbur called 'the finest day we ever had in practice.'"The brothers' aircraft were tested near Kitty Hawk and refined in a pasture near Dayton, Ohio, where their 1905 Flyer would become the first practical aircraft 110 years ago this year.

"It was at Huffman Prairie that summer and fall of 1905 that the brothers, by experiment and change, truly learned to fly. Then, also, at last, with a plane they could rely on, they could permit themselves enjoyment in what they had achieved. They could take pleasure in the very experience of traveling through the air in a motor-powered machine as no one had. And each would try as best he could to put the experience in words."

|

| McCullough at Wright State University with CBS's Rita Braver. |

This book takes us through the early life of the Wright Brothers, their success in designing and selling bicycles and their adventures in Europe, especially in Paris, at a time when they were courted by French, British and German governments and militaries – before the American military showed real interest in their achievements.

Eventually they received honors, memorials and accolades (and unfortunately acrimonious patent infringements) from Dayton to D.C. and from Le Mans to New York. We learn about their relationship with Otto Lilienthal, Chanute Langley, Charles Lindbergh, Alexander Bell, Glenn Curtiss and other friends and rivals.

Wilbur's flight in New York around the Statue of Liberty and above the departing Lusitania in 1909 is a standout. Orville saw the 1921 commissioning of his namesake USS Wright (AV/AZ-1), a ship that was captained by commanding officers that included Ernest J. King, Aubrey W. Fitch and Marc A. Mitscher and which fought in World War II in the Pacific. Orville lived long enough to see aircraft and bombers used extensively in WWII. The first USS Kitty Hawk (APV-1) was launched in 1941 and served throughout the Second World War. Another namesake, the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk II (CV(A) 63), was launched 57 years after the brothers' first flight, served nearly half a century, and was decommissioned in 2009. Read an extensive timeline history of the USS Kitty Hawk here.

Wilbur's flight in New York around the Statue of Liberty and above the departing Lusitania in 1909 is a standout. Orville saw the 1921 commissioning of his namesake USS Wright (AV/AZ-1), a ship that was captained by commanding officers that included Ernest J. King, Aubrey W. Fitch and Marc A. Mitscher and which fought in World War II in the Pacific. Orville lived long enough to see aircraft and bombers used extensively in WWII. The first USS Kitty Hawk (APV-1) was launched in 1941 and served throughout the Second World War. Another namesake, the aircraft carrier USS Kitty Hawk II (CV(A) 63), was launched 57 years after the brothers' first flight, served nearly half a century, and was decommissioned in 2009. Read an extensive timeline history of the USS Kitty Hawk here.When Neil Armstrong stepped on the lunar surface in 1969 he carried with him a piece of muslin from the Wright Brothers' 1903 Kitty Hawk Flyer.

Orville Wright (left) congratulates Maj. C.A. Lutz, United States Marine Corps flyer, who won the Curtiss Marine Trophy in Washington, May 18, 1928. Lutz averaged 157 miles an hour. (Photo by Harris & Ewing)

No comments:

Post a Comment